London’s Royal Academy of Art presents one of the most anticipated exhibitions of the year; a survey of the work created by the artist, designer, architect and activist Ai Weiwei, who is renowned for engaging with social issues in China ranging from State corruption, the defence of human rights and the conservation of cultural heritage. Ai’s ongoing clashes with the Pekín regime (in which censorship is commonplace) have cost him both his privacy and freedom as he has been put under surveillance, government restrictions and house arrest. He has also been the victim of assault and even imprisonment under such disparate charges as tax invasion and bigamy. Since his 81-day confinement in 2011, the artist has been unable to leave his own country, yet exhibitions of his work have been appearing all over the world.

China’s spectacular economic advances have been largely overshadowed by reports of the continuous cases of human rights abuses which are committed against the Chinese workforce, who are recruited into an unstable and poorly managed system of mass production. This repressive government is now facing a backlash from a group of some of China’s most notable intellectuals and artists who have developed various ways of resisting and challenging these abuses perpetrated by the flourishing regime. Ai Weiwei is one of their key representatives.

From art to politics

Art and politics runs in the family. Ai Weiwei (born 1957 in Pekín) was just one year old when his father, the writer Ai Qing – still considered one of China’s most influential contemporary poets – was accused of being a criminal during a state-imposed Communist repression aimed at silencing all intellectuals who opposed collectivisation in China. Ai Qing was sent to a military correction camp in the remote North-Eastern province of Manchuria where he was forced to do farm work in appalling conditions. Qing remained in Manchuria with his family right up until the death of Mao in 1976, which marked the end of his rehabilitation and the family’s return to their home in Pekín. This year would also mark the start of Ai Weiwei’s life as a student of Pekín Film Academy. This gave Ai the opportunity to rub shoulders with the likes of Zhang Yimou and Chen Kaige (key representatives of what is now known as the Seventh Art movement in China) as well as those artists in the same circles as Wang Keping, who along with others joined with Ai Weiwei to form Stars, the first political art group in China. 3 years later and Ai Weiwei unveils his first exhibition as a contribution to the ‘Defenders of Freedom of Expression’ group, in which he unofficially displays various watercolour pieces by hanging them from the banisters of the National Museum; they are taken down two days later by members of State Security. In the following years, the artist’s collective would become the target of State repression with some of its members persecuted and imprisoned and for this reason, Ai Weiwei decides to leave the country.

Trees at the entrance

During his ten years spent living in New York from 1983-93, Ai began to engage with Western culture. In this time he would pick up the habit of photographing everything of interest to him, leaving him with a collection of over 10,000 photos. By this time, he started being intimidated by the government as a result of his dedication to capturing images of police brutality in protests and selling them to the press. Photography aside, Ai also became fascinated with Pop Art, Conceptualism and Minimalism and as his work became increasingly influenced by Marcel Duchamp’s readymades, he decided to move away from painting and instead create three-dimensional pieces out of pre-existing materials. 10 years later, he returned to China and started economically translating his experiences of America into art. By creating these contemporary pieces, Ai began to consider art as a means of exploring and questioning Chinese society in comparison to what he found in America. It was at this moment that he forged a common thread which we can see running through many of his works: Ai Weiwei looks to create disturbing and paradoxical situations which bring reality into question and expose the flaws in Asia’s economic giant, now considered a potential global superpower.

A journey through the conscience

The RA exhibition displays Ai’s work right back from his return to China in 1983 through to his more recent pieces including ones which were especially commissioned for the occasion. The gallery boasts eleven impressive rooms containing a mixture of installations, photographs and smaller pieces which are essentially divided into three categories: projects made in response to a particular event, artwork inspired by Ai’s personal experiences and other works which express his own interpretation of China’s relationship with the West.

The first of Ai’s spectacular installations greets you as you enter the courtyard of the RA and consists of eight tree-like sculptures constructed from wood fragments of various species of tree, native to South China. The RA had to rely on crowdfunding to raise the £100,000 necessary to bring these fragments over, and did so by promising to reward any contributors with limited edition prints. According to the show’s commissioners, they received contributions from all over the world.

Straight, a memorial for the victims of Sichuan Province

After a brief overview of Ai Weiwei’s most iconic work in the 90s, we encounter the installation ‘Straight’ (2008-12), which is easily his most moving. ‘Straight’ epitomises the fusion of art with politics by sending out a global message of condemnation following the devastating earthquake which shook the Sichuan province in 2008. Ai signals this event as the moment in which he realised that his art could generate a greater collective conscience. The earthquake, whose victims were largely under the age of twelve, exposed an ugly truth behind the construction of school buildings which involved networks of government corruption as well as the embezzlement of public funds. Weiwei travelled to the earthquake site himself and compiled a list (the only one of its kind in China) of the 5,300 children who were killed, bringing the case to the government in Pekín and demanding answers. This move played a decisive role in Ai’s identification as a dissident activist and strengthened the authority he held as a social leader. Hence he became the target of State repression and in 2009, underwent treatment for a brain haemorrhage he sustained following a police beating.

The installation ‘Straight’, now on display at the RA, is composed of a spectacular central sculpture engaging a tombstone in the shape of tectonic plates, which is overlooked by giant panels on each wall bearing the names and personal details of each of the 5,300 victims. The central sculpture is formed from 200 tonnes of iron rebar which were illegally gathered from the rubble left by the collapsed buildings; these bars were all twisted and bent from the force of the earthquake. Various artists then worked to straighten each and every one by hand in order to recover its original shape, prior to the disaster.

He Xei (2013), river crabs as a symbol of censorship

Ai Weiwei communicates his ideas using an array of different contexts, scales and media, ranging from ancient wood, porcelain, marble and jade to scrap and waste material. Standing out amongst his smaller pieces are ‘Surveillance Camera’ (2010), which features a marble replica of one of the many cameras which monitor his studio-home, and ‘He Xei’ (2013), which is made up of a pile of red and green porcelain crabs that bring to mind his famous ‘Sunflower Seed ‘installation at the Tate Modern. These crabs are used to symbolise the State-censorship in China, particularly with regards to the Internet. Ever more striking, we encounter ‘Souvenir from Shanghai‘ (2012), a huge block of bricks inset with an archway of traditional Chinese wood, all constructed using remnants from Ai’s Shanghai studio which was demolished by the government despite them being the ones who commissioned it.

Two worlds collide…

His more ironic work comes in a form of a series of supposed Neolithic vases with the Coca Cola logo painted over them as a criticism of the way in which, after years of destruction, China now uses its heritage as a mere tourist attraction. This piece demonstrates Ai’s critical intent by bringing together China’s cultural heritage whilst also provocatively questioning the way in which his country is dealing with its recent exposure to the West.

On April 3rd 2011, while waiting for a flight to Hong Kong, Ai Weiwei was kidnapped by the Chinese government and held in solitary confinement at an unspecified location for 81 days. His experiences in captivity inspired the artist to mount a fresh challenge on Pekín’s authoritarian regime by creating an installation containing six iron dioramas in the style of bunkers with small windows through which to observe their interiors. Each interior features a set of hyperrealist fibreglass figures which represent his days spent in police custody. These figures, which were secretly made in China before being sent over to the UK, take the form of the artist himself and the two police officials who watched over him 24 hours a day from an 80cm distance whilst he ate, moved about and slept. They even watched him whilst he used the toilet.

Dioramas to relive Ai’s captivity

Ai Weiwei only just had his passport returned to him this July and although the British government initially denied him a visa due to his previous convictions, the issue was resolved and Ai could finally enter the UK in time to help with the opening of his great exhibition. Far from being satisfied with this gesture from the British, Ai led a march the very next day with his friend Anish Kapoor, the Anglo-Indian sculptor, in which protestors marched through central London, each with a bedsheet folded over their shoulder to demand that the EU increase its efforts in accommodating the thousands of refugees fleeing conflicts in the Middle East. Ai declared that “The UK is not contributing enough towards resolving this refugee crisis. If the UK fails to play its part, it just shows that it is no longer the power it once was. The rest of the world will see it as a weak country”. As you exit the exhibition you pass a spectacular chandelier which was especially commissioned for the show. Here, the artist reinvents the traditional chandelier (a Western symbol of wealth and opulence) by combining its crystals with bicycle wheels as a metaphor for the unnavigable world of Chinese labour, a contradiction to progress. All in all, this hugely important exhibition establishes Ai Weiwei as one of the most relevant and committed artists around, with his activism serving as a reminder to the way in which art can reach out to a wider audience and bring the world together for the better.

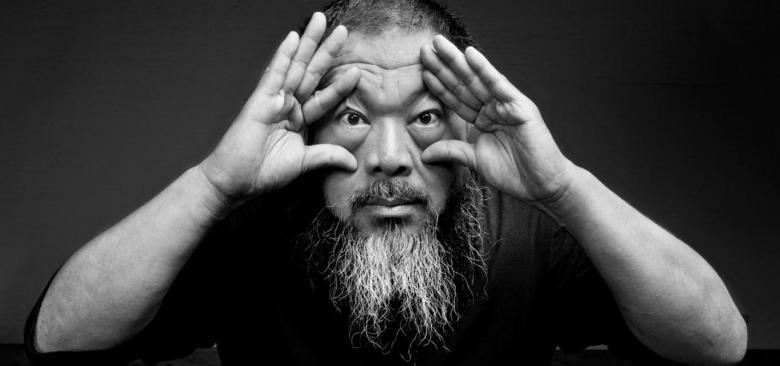

Cover image: Cover of the exhibition catalogue

Pictures: Dolores Galindo

Work © Ai WeiWei

———————————-

Ai WeiWei

Until next 13 December 2015

Royal Academy of Arts Burlington House, Piccadilly London W1J 0BD

[su_note note_color=”#eaeae9″]Translated by Danny Concha [/su_note]