There is no poet, outside his poetry. Never. Other voices, other incarnations may exist alongside the poet, in conflict with him, but the poet without his flesh, the flesh of his poetry, does not exist. And so his existence is not real; not composed of biographical facts. Facts are alien to poetry. And what transcends a poem is its own life, one that is new and different and almost without certainty. It is a sign. No biographical information alone can explain the poem’s existence, unless it too is of poetic fact.

Julian Bell, therefore, is a non-existent poet determined to disappear, to erase his poetic persona through the power of biography, following in the footsteps of his Anglo-Saxon predecessors like the wild Lord Byron.

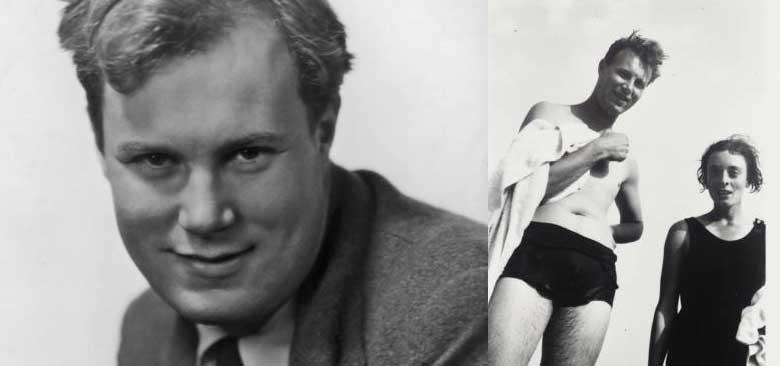

Julian Heward Bell was born on 4th February 1908 in Bloomsbury, London, the son of Clive Heward Bell and Vanessa Bell, sister of Virginia Woolf. He was named after his uncle, who had died in Greece aged 26. An ill omen, perhaps? A curse?

At the age of seventeen, before starting university, he was sent by his father, a lifelong Francophile, to Paris, no doubt with the hope that the young Julian would receive the same kind of cosmopolitan education that his father had enjoyed in his youth

He grew up in rural Sussex, with his brother Clive. At the age of seventeen, before starting university, he was sent by his father, a lifelong Francophile, to Paris, no doubt with the hope that the young Julian would receive the same kind of cosmopolitan education that his father had enjoyed in his youth. At the suggestion of a family friend, nephew of the painter Renoir, Julian was sent to Monsieur Pinault’s school, as well as sitting in on classes as a visiting student at the Sorbonne. But none of this could turn him into the worldly socialite that his father wanted. Nevertheless, it was through his long conversations with Pinault that he discovered the pleasure of literary and political debate. He read Voltaire, Racine and Anatole France. Pinault described himself as “a communist”, but it seems that this was more out of a desire to shock than from any real conviction. Even so, his time with Pinault strengthened Bell’s theoretical socialist convictions far more than staying in England could have done. Paris, and above all Maupassant, had made a poet and a politician out of him.

On his return he went up to King’s College, Cambridge where he became a member of the Cambridge Apostles, a secret society founded in 1820 that fostered intellectual debate. It was during his time in Cambridge he published his first book, Winter Movement (1930). It was well-received, and Bell was even compared with W.H. Auden, who had just published his Poems. He was described as a Romantic, both because of his themes and by opposition to the esoteric epic poetry still very much in favour in England at the time. Yet Julian was neither happy nor secure in his work. His technique was outdated and he didn’t know how to go about developing a new one, how to find his own voice.

His Aunt Virginia, mentor, friend and advisor, had detected this in these early poems and declared: “He is no poet ”

His Aunt Virginia, mentor, friend and advisor, had detected this in these early poems and declared: “He is no poet” (2). On the other hand, poets were somewhat rare in the Bloomsbury Set (3). Eliot would describe him as the poetic, political member of the group, despite the fact that he was already a fully formed author by the time he joined, at the end of the First World War.

It was also during his university days that he came into contact with the Cambridge Five, the circle of English spies recruited by the Soviet Union. Although it has never been proved that he was actively involved in the group, he did maintain close relations with two of its members: Anthony Blunt and Guy Burgess. It was probably his growing political awareness that gradually separated him from his poetic vocation. This was a statement of independence both in his morals and from his family, a gesture of self-assertion in the face of bourgeois Bloomsbury and its political dilettantes.

In 1935 he travelled to China to take up a post as Professor of English at the University of Wuhan. Whilst there, he wrote a series of letters about his relationship with a married Chinese woman, identified only by her initials. In 1999 the writer Hong Yin wrote a novel based on these letters, entitled K:The Art of Love, which she was forced to rewrite after a court declared it defamatory, eventually publishing her work in 2003 under the title “The English Lover”. Bell did not finish his residency in China, as he decided to return to Europe to enlist in the International Brigades and fight in Spain. Ironically, it was in the same year, 1935, that he published the prologue to the anti-war book We Did Not Fight: 1914-1918 Experiences of War Resisters. The following year, he published a collection of poems entitled Work for the Winter (1936), which was to be his last work.

Various family members and friends discouraged Bell from enlisting: David Garnett, Kingsley Martin, Stephen Spender and E.M Forster were among those who attempted to dissuade him, suggesting that he join up as an ambulance driver for the British Medical Aid Unit instead. He had become the pacifist who went to war.

The boy had given way to the poet, and now the poet to the warrior, a tradition poetic in itself. He had no shortage of forebears, either British or Spanish: Jorge Manrique, Garcilaso, Francisco de Aldana, Miguel de Cervantes, Sir Philip Sidney, Sir Henry Howard, Edmund Spenser, Thomas Wyatt, Lord Byron, to name but a few of the most celebrated.

Can we do justice to someone, to their life, by limiting it to a paragraph, to a moment, a decision, either rash or well considered?

Can we do justice to someone, to their life, by limiting it to a paragraph, to a moment, a decision, either rash or well considered? Is it cynical to speak of liberty, of life, in an obituary? In essence, what we have here is a question of Julian and his choice, what he considered to be action, the rupture with his bourgeois Bloomsbury dilettante past and transformation into a new man, magnificently alive and committed to the moment; the anti-poet, his finest work.

Finally fully self-aware, in the heart of the action, Julian was happy like never before (4), something that was clear to his family and other members of his brigade. And so he was no longer a poet when, on the morning of 18th July 1937 at Villanueva de la Cañada (5), a piece of shrapnel, like a rotten apple, spelled a permanent end for his passport, and for his heart. Both were visible through the wound in his chest. There was nothing that could be done. In his own words “I always wanted a mistress and a chance to go to war, and now I’ve had both”. He died the same day at El Escorial, reciting Baudelaire (6) in French , after twelve hours of agony.

Is violent death the final and most emphatic poetic fact, when it is voluntarily accepted? Even when all poetic identity has been cast aside?

—————————————————————————-

(1) Spanish Bombs: The title of a song by The Clash from the album ‘London Calling’, an homage to the International Brigades of the Spanish Civil War.

(2) Extract from a letter published by The Paris Review.

(3) The name Bloomsbury set or group is usually referred to a group of British intellectuals during the first third of the twentieth century highlighted in the literary, artistic or social grounds. It is well appointed taking the name of the surrounding neighborhood of London and the British Museum where he lived most of their members.

(4) According to Richard Rees a fellow ambulance driver at the Battle of Brunete.

(5) The Battle of Brunete: a series of operations taking place from July 6th to the 25th, 1937, in this and other towns to the west of Madrid, as part of the Spanish Civil War.

(6) As reported by Archie Cochrane: doctor of the International Brigades who attended Julian Bell in El Escorial.

Bibliography:

Bell, Quentin (1996) “Bloomsbury Recalled”, New York: Colombia University Press. (Julian’s brother’s reflections on the literary world and social milieu of their family).

Laurence, Patricia (2006) “Julian Bell: The Violent Pacifist”, London: Cecil Woolf Publishers. (Part of the Bloomsbury Heritage Series, by a professor of English at City University, New York).

Palfreeman, Linda (2012) “¡Salud!: British volunteers in the Republican Medical Service during the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939”, Brighton: Sussex Academic Press.

Stansky, Peter and Miller Abrahams, William (1994) “Journey to the Frontier: two roads to the Spanish Civil War”, Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Stansky, Peter and Miller Abrahams, William (2012) “Julian Bell: From Bloomsbury to the Spanish Civil War”, Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

[su_note note_color=”#eaeae9″]Translated by William Carter[/su_note]