Every now and then my eyes are drawn to an object that, for years, played a major role in shaping my ideas about the world. It is a Sony radio receiver, designed for exploring the world of shortwave programmes. I keep it on a shelf near where I write as a piece of nostalgia. I have used it to listen to all sorts of things, but mainly the BBC.

Every now and then my eyes are drawn to an object that, for years, played a major role in shaping my ideas about the world. It is a Sony radio receiver, designed for exploring the world of shortwave programmes. I keep it on a shelf near where I write as a piece of nostalgia. I have used it to listen to all sorts of things, but mainly the BBC.

Even when I was a teenager, my family and I would wait until nightfall so that ionospheric reflection would help the waves of Radio Paris and the BBC to reach us.

My passion for radio is not a consequence of my profession – although I have worked in the field for nearly fifty years – but rather of being a Spaniard brought up in the post-war era, in the “Long Night of Stone” that Celso Emilio Ferreiro portrayed so vividly in his poetry. At first, I used to listen to my radio under the bedspread for fear of alerting the neighbours and provoking a call to Franco’s secret police. Even when I was a teenager and had grown out of such anxieties, my family and I would wait until nightfall so that ionospheric reflection would help the waves of Radio Paris and the BBC to reach us. Thanks to an old Philips “magic eye” receiver, we could hear at home everything the censors had barred from the Spanish media. Franco’s forces of repression could not fight against the science of telecommunications, although they tried, mainly by using powerful transmitters to emit noise at the same frequency as the clandestine Radio Pirenaica.

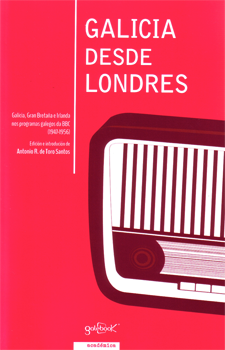

From that night of stone that was incredibly long (Hitler ruled for twelve years, Franco for forty), I was left with a love of listening to programmes from transmitters with the power to broadcast over great distances. Eventually, I installed antennas in my house which had enough “gain” (power concentration) to pick up weak signals. Typical engineer behaviour. Galicia from London, Galicia, Great Britain and Ireland in the programs “galegos da BBC”. Antonio R. de Toro Santos

As technical director of the CRTVG, Galicia’s public radio and television company, I was involved in a study concerning Radio Exterior de Galicia, a project intended to facilitate communication between Spain and its expatriates and sailors, like Radio Exterior de España, but in Galician and with its own programme schedule. The conclusion drawn from the study was what we expected: even if we only wanted to broadcast from Galicia to Western Europe, the Atlantic and Latin America, we would still need to produce hundreds of kilowatts of power using expensive systems, on the kind of site that would be difficult for us to obtain. Global coverage for the many Galician sailors serving in fleets in faraway places like the Indian Ocean was simply out of the question. A change in political opinion put paid to the project and it was not considered again; mainly because the Internet was expanding and, with it, the World Wide Web was developing into an ever more solid platform for transmitting information. Even in the days of the simple modem, it was possible to listen to the major radio stations online. Back then, I used to switch between the air waves and the telephone line. I remember how I enjoyed measuring the delays in transmission. The BBC’s time signals would arrive six seconds earlier on the radio than on the computer.

If we survey the history of how web-based audiovisual services have developed, we can see that as network capacity grew, the introduction of online transmission techniques resulted in a product of increasingly high quality being sold at an unchanging price. Each year, more radio stations joined the trend: it was no longer just the biggest stations that reached the homes of expats with access to the Internet.

Who, then, was still listening to shortwave radio programmes? Sailors, missionaries, overseas voluntary workers… in the jungle, in the desert, at sea…

Last year saw the rise of controversy regarding Radio Exterior de España, which was no longer being broadcast solely via shortwave, but also online and via satellite. Calculations showed that ceasing to broadcast from terrestrial transmitters would mean making a saving of one million Euros per year (and cause trouble for the electricity company providing the energy to transmit the electromagnetic waves, of course).

And who were the objectors? Not the expats living in “civilised” places, but the sailors. Anyone who has experienced life on board a fishing boat will know how the crew work to a constant accompaniment of shortwave radio, broadcast from speakers above and below deck. So much pressure was put on Radio Nacional de España that they backed down to some extent, offering limited coverage and reduced programme schedules.

Who, then, was still listening to shortwave radio programmes? Sailors, missionaries, overseas voluntary workers… in the jungle, in the desert, at sea…

All the same, it was just a compromise, an attempt to calm people’s fury. A technical solution for this kind of issue does exist: a high-quality Internet connection available anywhere on the planet, made under the watchful “gaze” of communication satellites 37,000 km up in the sky. If you compare the cost of a reasonably-priced data package with that of the fuel for the average fishing trawler, it does not seem such a great expense to make a crew of sailors feel “at home” by allowing them the services you can enjoy with WiFi on land.

Which brings me to the conclusion that however romantic shortwave radio might appear, however fond the memories it conjures up for you might be, comparing it to what the Web can offer is like remembering fax machines (or even telexes or telegraphs) every time you send an email. My wish, then, is that people on boats, or in places “where the Devil lost his poncho” (to use a lovely Argentine saying) will “sign up for satellite” (that’s an engineer’s saying) and become better connected with the faraway country that loves and misses them.